Generative AI Systems (GenAISys)¶

What are Generative AI Systems (GenAISys)?¶

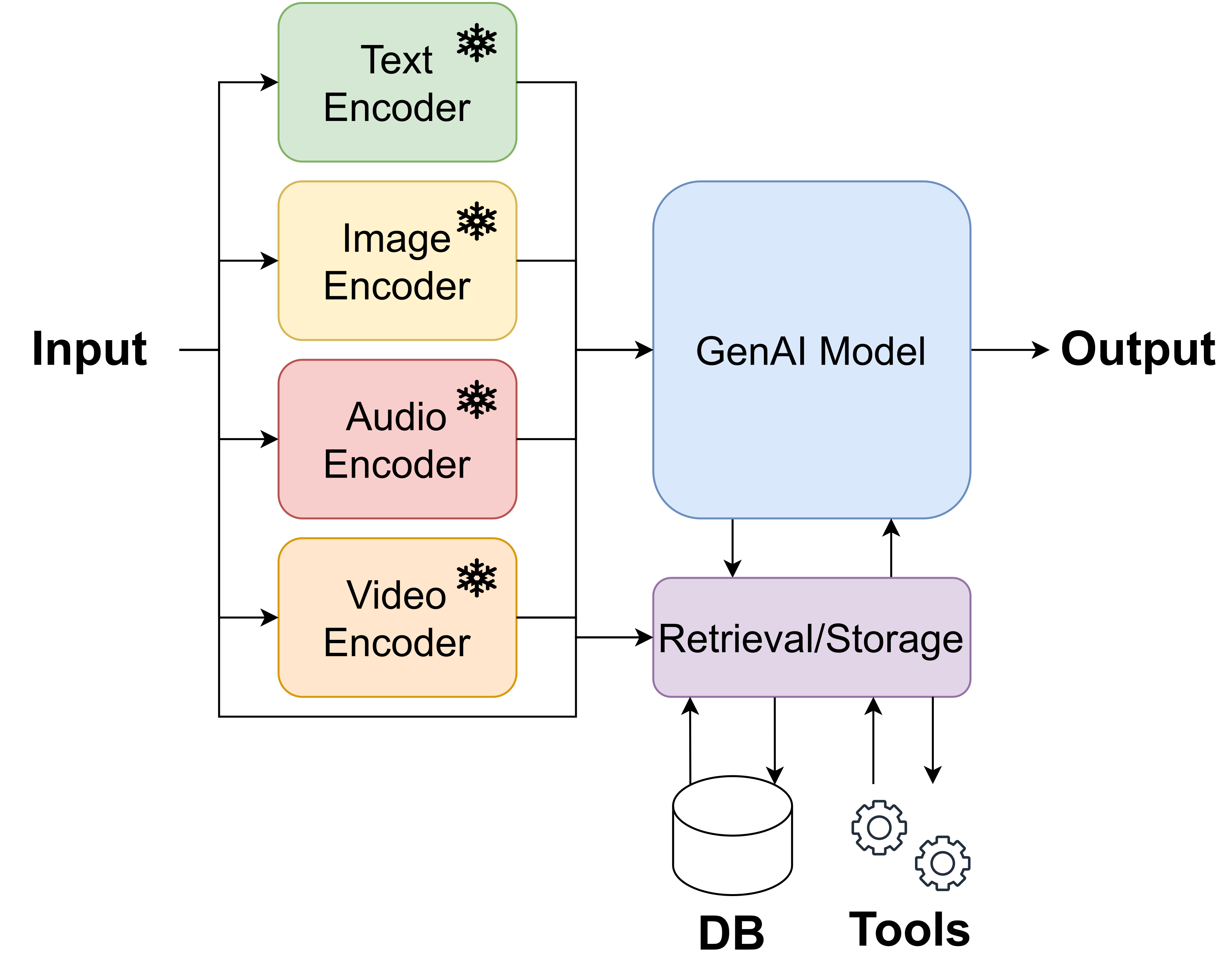

Intro LLMs opened doors to the next level of applications, allowing communication with machines using natural language. This is definitely a technological jump but also a great leap in the way we think about AI. The recent developments in GenAI, e.g., in the GPT family (GPT-4V: GPT-4 with Vision) or in the Google-based models (e.g., Gemini), brought multimodal learning in DL back and showed great promise in using LLMs as multimodal systems. Currently developed LLMs are capable of processing various data modalities (not only text but also images, audio, and video) and generating different data types! As a result, it becomes more appropriate to talk about GenAI systems rather than LLMs. Text (or natural language) constitutes communication means, instead of pre-defined formal protocols, and modality encoders play the role of I/O interfaces for processing various data sources. However, we can go even further and can attach a database (or, in particular, a knowledge graph) or external specialized tools (e.g., a calculator, an app for finding a route from A to B) that communicate with the system through a module for information retrieval and storage. An example of such a system is a tool-augmented Seq2Seq model proposed by (Parisi et al., 2022) that uses a fine-tuned T5 LLM as a backbone to deal with inputs and outputs to and from some external tools. A more specific use of an LLM with an external tool is a system for chemistry (Bran et al., 2023) is based on external databases and tools for providing reliable answers and drawing molecules, among other features.

In the following, we will look into various systems using Generative AI modules that we will refer to as Generative AI Systems (GenAISys). It is interesting to discuss these systems at a high level since we are far from the full understanding of their building blocks (i.e., neural networks or even their simplest units). As the community, we have a good feeling that the strength of DL lies in its compositionality (Bereska & Gavves, 2024; Swan et al., 2022), but we still need to accept many claims to be hypotheses. Nevertheless, it should not stop us from discussing compositionality at a higher level, similar to control theory, or more broadly, systems science and engineering (Bubnicki, 2005). Let us do that then!

GenAISys: A general architecture Talking about systems immediately brings to mind multiple modules, some components combined together to solve a set of goals. The discussion might be a bit blurry at times because the question is the following: Is a composition of two functions with a single line of code each a system already? Yes, because systems are composed of distinguished parts or, to put it differently, systems are complex things that can be assembled out of simpler parts. An interesting perspective on systems and compositionality provides category theory (Fong & Spivak, 2018), if you are interested, my curious reader. However, here we will continue in a more intuitive manner.

We already mentioned what GenAI systems are built of, so let us make it more specific then. A GenAISys consists of the following parts:

- Data encoders (DEs): All input (raw) data are processed using models that encode them into tensors. Typically, these encoders are pre-trained and kept non-trained (frozen). We can use any Foundation Model (FM) as an encoder, e.g., BERT for text encoding, ConvNeXT (without the predictive head) for image encoding, etc. Encoders could be composed of other modules (encoders) as well. For instance, speech could be transformed into text (e.g., using Whisper) and then text could be represented as a tensor (e.g., using BERT). Data encoders play a crucial role in formulating GenAISys and their introduction was a catalyzer for the development of GenAI systems as we know it now.

- GenAI Model (GeM): The central unit of a GenAISys is a GenAI model (e.g., an LLM) that processes (encoded) input data, communicates with external memory (a database) and external tools, and generates an output. It is the core part of the whole architecture. It can have its own short-term memory (a cache), e.g., in the form of available input tokens, and built-in instructions for communicating with other components. Moreover, it can be equipped with other (sub)models carrying out other tasks, e.g., Named Entity Recognition (NER) for detecting specific instructions in inputs. In the simplest form, it could be trained in such a way that specific instructions in natural language trigger specific actions like running a calculator. Overall, a GeM can be a complicated system by itself, comprising multiple modules including separate models.

- Retrieval/Storage module (R/S): This module serves an extremely important function to assist GeM with retrieving facts (long-term memory) but also utilizing inputs processed by DEs. Additionally, this module can has own models (e.g., BERT to embed a part of the input text of an internal instruction) and sets of instructions (e.g., routing algorithms).

A general scheme of GenAISys is presented in Figure 1. Please keep in mind that this is a simplified architecture that highlights only the main components. Each block could consist of multiple submodules, models, and procedures (algorithms). It is also no surprise that the diagram looks like the general architecture of a computer. After all, such architectures are quite natural. However, unlike a computer, GenAISys consists of trainable components and, as a result, is extremely flexible in the sense of its functionality.

Training of a GenAISys is non-trivial since all components are, in principle at least, trainable. One can imagine training GenAISys end-to-end, however, it is infeasible for currently used hardware. Nowadays, a widely applied solution is to take advantage of foundation models that are pre-trained separately to formulate DEs and an R/S. Eventually, only a GeM is trained. But, with the improvement of hardware, and probably with new training schemes, GenAISys will be trained in a better way and, eventually, will get better through the utilization of multiple data modalities at the same time. I fully agree with you, my curious reader, this general scheme in Figure 1 resembles a map of the functions of the human brain. At this point, we are definitely close to applying a coordinate descent algorithm that optimizes the whole system one modality (or a block) at a time. This would keep the complexity at a relatively low level, no greater than what we have right now. However, the main issue is the potential forgetting of previously learned representations. We do not have fully satisfactory continual learning methods, but we are making progress (Mundt et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024). Once this problem is solved, we will get a real breakthrough in AI!

Examples of GenAISys¶

Following the general scheme for GenAISys in Figure 1, we can indicate how currently used Generative AI approaches fit this scheme. We focus on Large Vision Models and a specific LLM-based solution for reliable text generation. There are many more examples, but once you get familiar with the most successful ones, you will definitely be able to see this scheme in other models, my curious reader.

RAGs The main drawback of decoder-based LLMs is hallucinating when a prompt takes the model away from its "comfort zone" (i.e., from regions where training data lie in the representation space). This could be fixed to some degree with proper fine-tuning, however, LLMs have the tendency to make up or skip some facts. Since their responses are typically very colorful with distinctive and unusual wording, human beings can miss some deficiencies and false statements. Therefore, sometimes, I refer to LLMs as Lying Language Models. In some applications, there is no place for fake news or, in general, outcomes cannot be untrustworthy. For instance, in health-related situations, medicine, drug discovery, or manufacturing (e.g., diagnostics), there is simply no space for made-up facts. Therefore, even though generative LLMs are so hyped, they do not pose a possible solution due to their high risk of hallucinating.

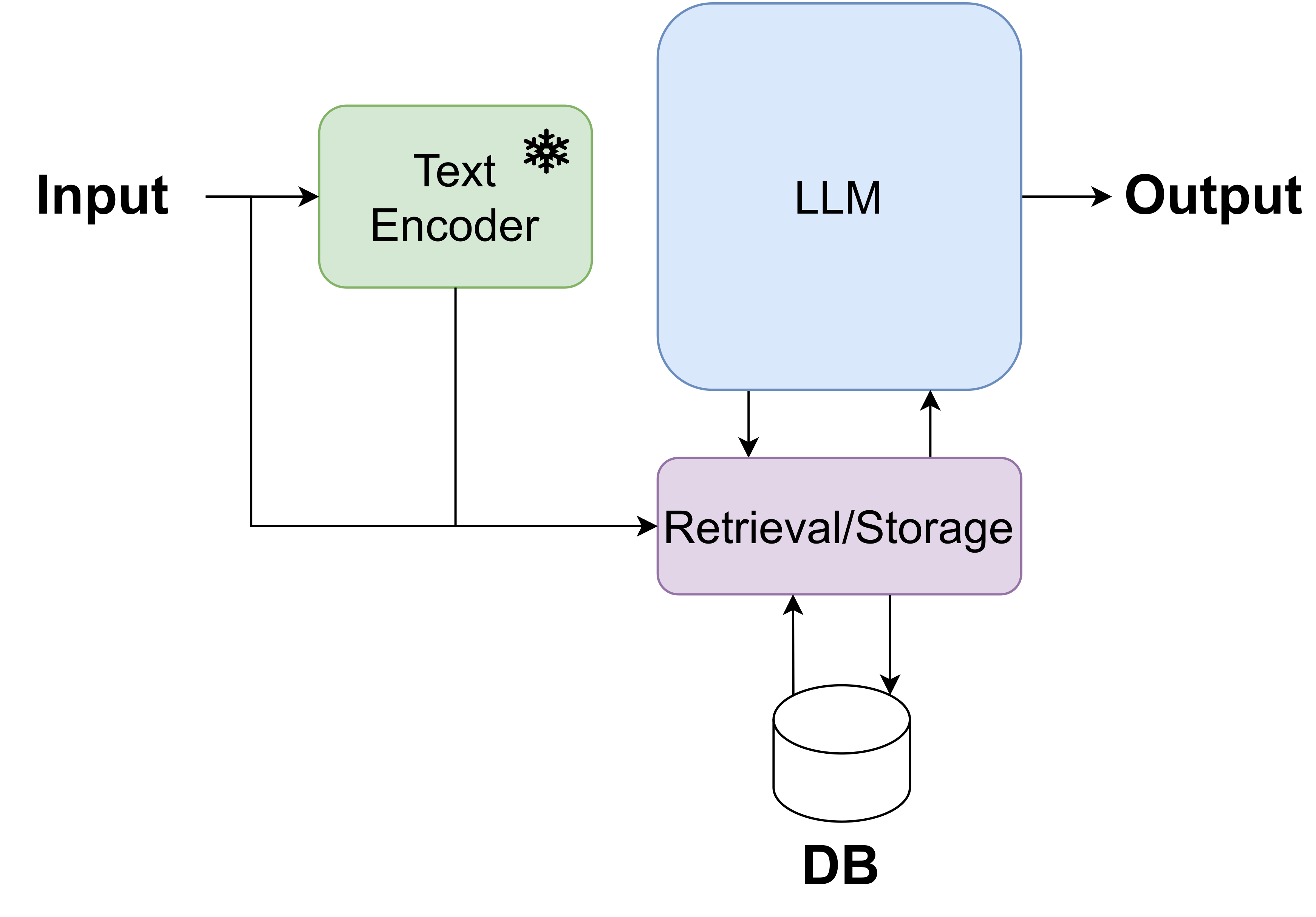

A huge breakthrough, especially in real-life applications, came with Retrieval Augmented Generations (RAGs) (Lewis et al., 2020). The idea is based on utilizing two LLMs: an encoder-LLM and a decoder-LLM, and a database of texts. The encoder-LLM is used in two ways: (i) for embedding all texts in the database, and (ii) for embedding an incoming query. For a new query, the closest documents are picked based on the distance between the embedding of the query and the embeddings of the documents in the database. Eventually, the closest documents, together with the query, are passed to the decoder-LLM to generate an outcome. Since the outcome is based on the decoder-LLM and real documents, there is a much lower chance of hallucinations. Moreover, with a bit of tweaking around, the RAG could rely heavily on facts provided during the retrieval stage.

The diagram for a RAG is presented in Figure 2 and it corresponds very closely to the general scheme of GenAISys in Figure 1 where the decoder-LLM is the GeM, and the encoder-LLM is the DE and it is also used as a part of the R/S module.

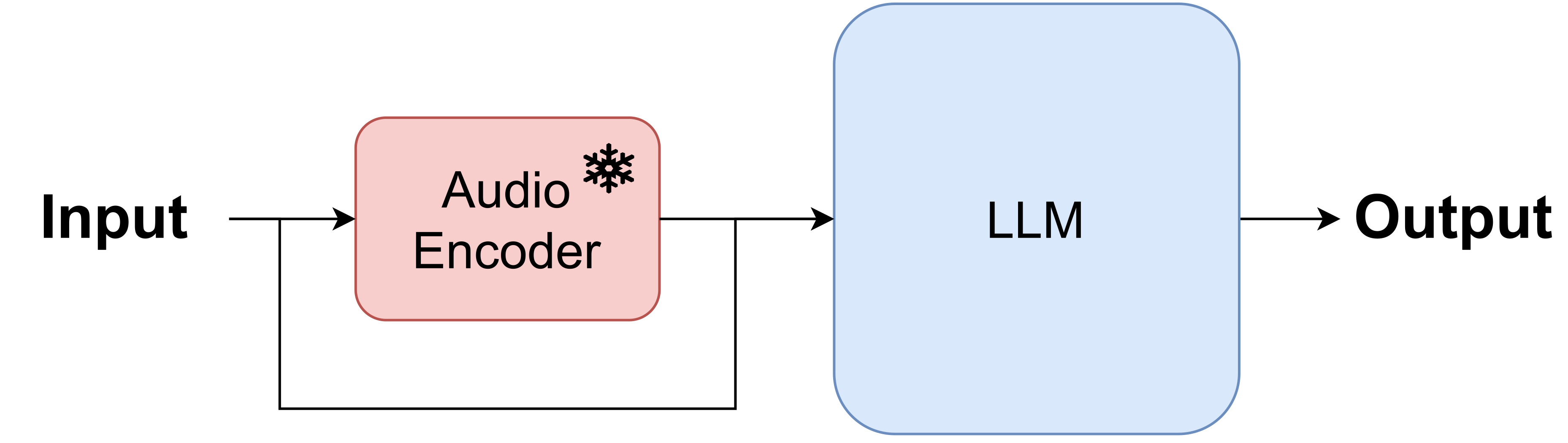

Speech2Txt A great example of a GenAISys for transforming speech to text is Whisper (Radford et al., 2023), an encoder-decoder transformer with a specific form of the encoder that first represents raw speech (audio) using a log-magnitude Mel spectrogram before being fed to a encoder-transformer for processing audio signal and then to a decoder-transformer for generating text. The model is an automatic speech recognition system with 39M weights (a tiny version) to even 1.55B weights (a large version). It was trained on 680,000 hours of multilingual and multitask supervised data collected from the web. This model achieved SOTA performance at the time of its release and still it remains one of the top Speech2Txt models available. The tiny version could even deployed on edge devices. Whisper is a great example of how GenAISys can be formulated and how important it is to combine various components together for more advanced tasks like automatic speech recognition.

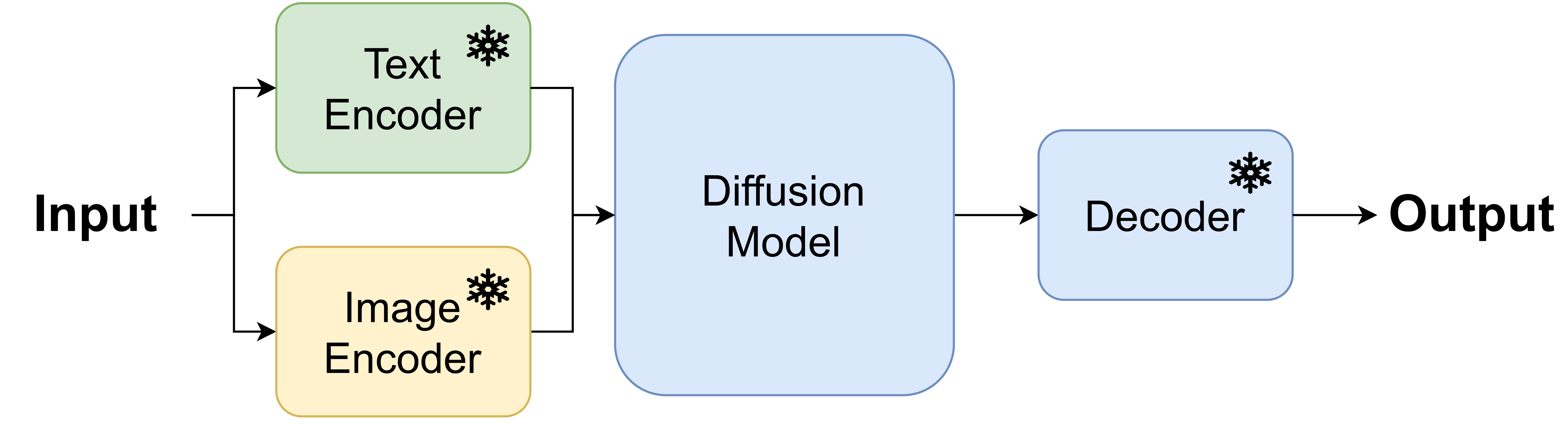

Large Vision Models (LVMs) Beside LLMs, Large Vision Models (LVMs) are perfect examples of GenAISys. There are many models that fall under the umbrella of Img2Img or Img2Txt, but the most popular these days LVMs are Txt2Img. Since the original paper on latent diffusion models (Rombach et al., 2022), the resulting models like Stable Diffusion 2 and very recent Stable Diffusion 3, are widely used for generating images for a given prompt. Latent diffusion models (Stable Diffusion) or Dalle 2 (Ramesh et al., 2022) with a diffusion-based prior fit perfectly a scheme in Figure 4.A. Comparing these LVMs to a general GenAISys, a text encoder and an image encoder (for either training or reconstruction) are DEs while a combination of a diffusion model and a decoder is a GeM. These models do not use any database or external tools, however, it is possible to use those to modify images somehow.

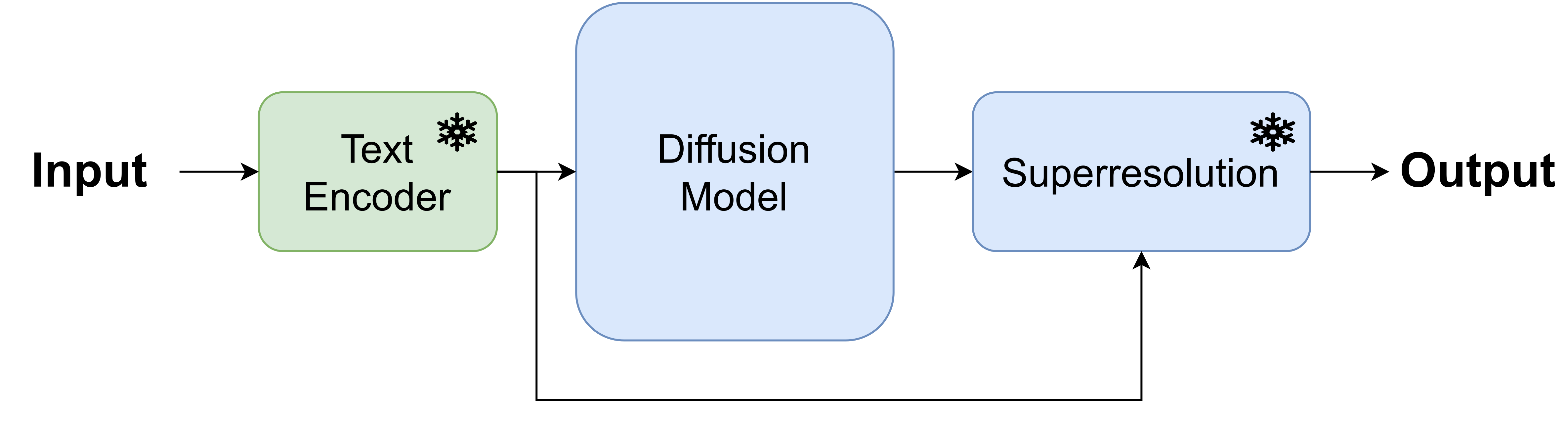

Another example of an LVM in the form of Txt2Img is ImaGen (Saharia et al., 2022) which uses a T5-based text encoder and a diffusion model together with superresolution blocks. The corresponding architecture is presented in Figure 4.B (the superresolution module consists of multiple steps, going from 64x64 images to 1024x1024 images). Again, this is a complicated GenAISys even though it is composed of three blocks but it has about 13B weights (11B weights for T5, about 2B weights for a UNet used in the diffusion model and the superresolution module) which is a large model in terms of the number of weights.

A

B

Future of AI is GenAISys¶

The idea of using LLMs as a backbone for Operating Systems and agents as applications has attracted a lot of attention (Ge et al., 2023). Here, we consider general systems with various GenAI-based components, not only LLM-based compartments. Either way, moving towards GenAI-based (operating) systems seems like the future, and the next step of cloud-based systems. Indeed, GenAISys can be deployed locally, but also in a cloud server; or as a hybrid (e.g., a GeM, a cache storage, and DEs are local but external tools and storage are in a cloud). The last option can be especially appealing for manufacturing since all real-life operations must be executed in real-time while data storage and other operations are carried out by external services (or agents).

Another idea that is pretty hyped these days is Agentic AI, i.e., the development of GenAISys-based agents operating in an autonomous manner. This idea is pushed by many Big Tech players. For instance, Microsoft proposed a framework for conversational LLM-based agents called AutoGen (Wu et al., 2023). OpenAI sees their chatbots (incl. ChatGPT) as agents and by equipping them with various tools and features, they could serve as co-pilots (i.e., assisting a human operator by proposing partial solutions) or auto-pilots (i.e., assisting human operators by proposing complete solutions). The analogy here corresponds to controlling a plane and a co-pilot helps to stabilize a flight while an auto-pilot takes care of flying. In both cases though a human pilot can take over at any point.

My curious reader, I hope I managed to present you with a wonderful world of (deep) generative modeling and convince you that Generative AI Systems are inevitable next steps in the evolution of AI. I dare even say that they will not only assist in many jobs, ranging from office jobs, healthcare, and education to the industry like manufacturing but also will lead us to formulate the first true AI. There are many other aspects like embodied AI, but in my (not so humble) opinion, GenAISys are a must to create an artificial brain for embodied or not machine. But we will see for the distant future (in the AI world, it means the next 6 to 12 months) will bring. Either way, I am sure we live in extremely fascinating times, totally unprecedented.

References¶

(Bereska & Gavves, 2024) Bereska, L., & Gavves, E. (2024). Mechanistic Interpretability for AI Safety--A Review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14082.

(Bran et al., 2023) Bran, A. M., Cox, S., Schilter, O., Baldassari, C., White, A., & Schwaller, P. (2023). Augmenting large language models with chemistry tools. In NeurIPS 2023 AI for Science Workshop.

(Bubnicki, 2005) Bubnicki, Z. (2005). Modern control theory. Berlin: Springer.

(Fong & Spivak, 2018) Fong, B., & Spivak, D. I. (2018). Seven sketches in compositionality: An invitation to applied category theory. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.05316.

(Ge et al., 2023) Ge, Y., Ren, Y., Hua, W., Xu, S., Tan, J., & Zhang, Y. (2023). LLM as OS, Agents as Apps: Envisioning AIOS, Agents and the AIOS-Agent Ecosystem. arXiv e-prints, arXiv-2312.

(Lewis et al., 2020) Lewis, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., Petroni, F., Karpukhin, V., Goyal, N., ... & Kiela, D. (2020). Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33, 9459-9474.

(Mundt et al., 2023) Mundt, M., Hong, Y., Pliushch, I., & Ramesh, V. (2023). A wholistic view of continual learning with deep neural networks: Forgotten lessons and the bridge to active and open world learning. Neural Networks, 160, 306-336.

(Parisi et al., 2022) Parisi, A., Zhao, Y., & Fiedel, N. (2022). Talm: Tool augmented language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.12255.

(Radford et al., 2023) Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Xu, T., Brockman, G., McLeavey, C., & Sutskever, I. (2023). Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 28492-28518). PMLR.

(Ramesh et al., 2022) Ramesh, A., Dhariwal, P., Nichol, A., Chu, C., & Chen, M. (2022). Hierarchical text-conditional image generation with clip latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125, 1(2), 3.

(Rombach et al., 2022) Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P., & Ommer, B. (2022). High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 10684-10695).

(Saharia et al., 2022) Saharia, C., Chan, W., Saxena, S., Li, L., Whang, J., Denton, E. L., ... & Norouzi, M. (2022). Photorealistic text-to-image diffusion models with deep language understanding. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35, 36479-36494.

(Swan et al., 2022) Swan, J., Nivel, E., Kant, N., Hedges, J., Atkinson, T., & Steunebrink, B. (2022). The Road to General Intelligence (p. 136). Springer Nature.

(Wang et al., 2024) Wang, L., Zhang, X., Su, H., & Zhu, J. (2024). A comprehensive survey of continual learning: Theory, method and application. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

(Wu et al., 2023) Wu, Q., Bansal, G., Zhang, J., Wu, Y., Zhang, S., Zhu, E., ... & Wang, C. (2023). Autogen: Enabling next-gen llm applications via multi-agent conversation framework. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.08155.